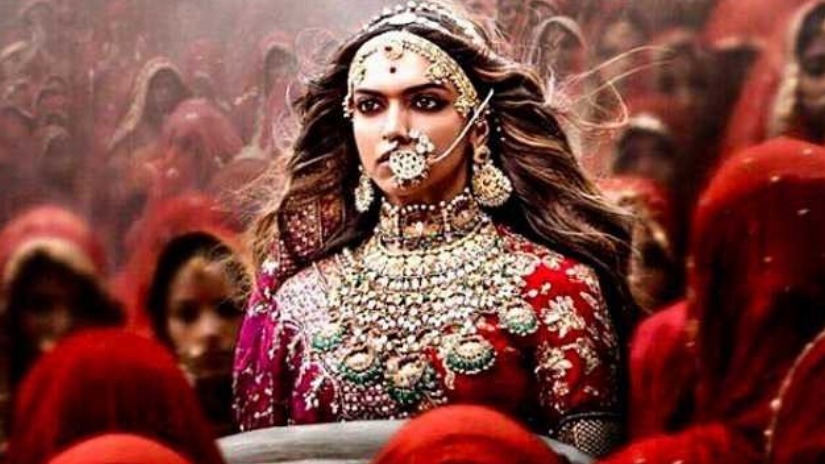

Besides being the latest in the saga surrounding Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s upcoming Padmavati, the news of its 1 December release ‘voluntarily deferred’ makes it the second high-profile film to get postponed in recent times. A few weeks ago, the Rajinikanth-Akshay Kumar-Amy Jackson starrer 2.0 was also pushedfrom a Diwali 2017 release to a Republic Day 2018 weekend release on account of the visual effects taking longer than anticipated.

Although the two films appear to be postponed for entirely different reasons, there are chances that Tiger Zinda Hai, that is supposed to hit the theatres on Christmas Day next month, could also get pushed to a new date.

One of the reasons for Padmavati, and also Tiger Zinda Hai’s release getting deferred could also have to do with the Central Board of Film Certification’s (CBFC) decision to adhere to the ‘submit your films 68-days in advance’ rule in order to obtain the censor certification on time. The rule was always there but studio officials dealing with the CBFC in the past have said that there existed a difference between the rule and the convention and for all practical purposes, the industry always went to CBFC three weeks before the release date.

While the trade appears to be baffled at an already existing rule been brought to the forefront, the manner in which Bhansali screened Padmavati for selective media outlets and individuals without obtaining the CBFC certificate has not gone down well with CBFC Chairman Prasoon Joshi. The delay in CBFC certifying the film was supposedly on the account of the original set of documents accompanying the film were incomplete and Joshi found what the Padmavati makers were doing to be ‘disappointing’.

The manner in which films get made in India also impacts its release. Here, the adage of brilliance not being a thing that could be rushed assumes a whole new meaning. Things such as permissions or clearances to shoot at public spaces, which, at times, can cause endless delays, wreak havoc on the schedules as does the relationship status between a film’s lead couple. There have been instances where films were announced with a real-life couple and the fate of the film rode entirely on the course of the relationship; if the couple, say such as Rajesh Khanna and Tina Munim, parted ways during the course of the filming, the chances of it never seeing the light of day were next to impossible. This is what happened with Souten Ki Beti that Saawan Kumar Tak had shot a considerable portion of with the two but had to rejig the film when the couple separated.

At times, the simple act of coordinating the availability of actors otherwise called ‘dates’ led to many producers losing hair and even health. Endless delay, like in the case of K Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam or Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah that took 16 and 14 years respectively to get made, is perhaps as legendary as the films themselves. Asif originally cast Chandra Mohan, DK Sapru, and Nargis for the roles of Akbar, Salim, and Anarkali when he started shooting the film in 1946 and even Amrohi had started Pakeezah with Ashok Kumar and Meena Kumari as the leads but the time the films released, they transformed into something else from the original ideas. If budgetary constraints were primarily the reason for the delay in Mughal-e-Azam, the personal relationship between Amrohi and Meena Kumari, who were married and later divorced, during the course of Pakeezah was what charted the course of the film’s making.

Sometimes the ‘mood’ of an artist is also the reason for delaying a film. In an illuminating article that he penned for the January 1957 edition of Filmfare, the iconic Kishore Kumar wrote how “this acting business” was filled with sham and pomposity and blamed an exaggerated notion of the self for it. The legendary singer-actor shared nuggets about stars trying to get into the right mood to emote while everyone waited endlessly and suggested to producers to simply wave a five thousand rupee cheque from behind the camera to get actors to evoke any mood!

Amongst other things such as budget that a delay in the making of the film could affect, its influence on the novelty of the project is by far the most significant. Take for instance Andaz Apna Apna. The film took almost five years to get made and by the time it released, the appeal of watching Aamir Khan and Salman Khan share the screen became stale. The manner in which the film remained in news during the course of its making made the project familiar with the audiences and when they finally saw the film, they could not wrap their minds around the reasons for the delay. It was not like Andaz Apna Apna was a Mughal-e-Azam or even Love and God, the film based on Laila-Majnu that K Asif began in 1962 with Guru Dutt (who died midway and was replaced with Sanjeev Kumar). Following Asif’s death in 1971, the film finally came out in 1985 when KC Bokadia completed it!

Aamir Khan and Salman Khan in a still from Andaz Apna Apna

Actors vying to make the most of the perfect release window — long weekends, holiday season or festivals, often see them constantly shift release dates such as Shah Rukh Khan postponing Raees to leave the Eid release spot for Salman Khan’s Sultan. One of the noticeable difference in films getting delayed back in the 1970s or 1980s where a couple of years was considered normal for any film, is the announcement of a release date even before a film is ready.

A recent example is Kabir Khan’s new film on India’s 1983 cricket world cup with Ranveer Singh already being announced as an April 2019 release. Irrespective of the reasons, any delay when it comes to big budget productions such as Bhansali’s Padmavati or Abhishek Chaubey’s Udta Punjab only increases the buzz surrounding them and while the delay somewhere makes it certain that the public knows about it, one, however, can never be certain if the public does care.

source by:-firstpost

Share: